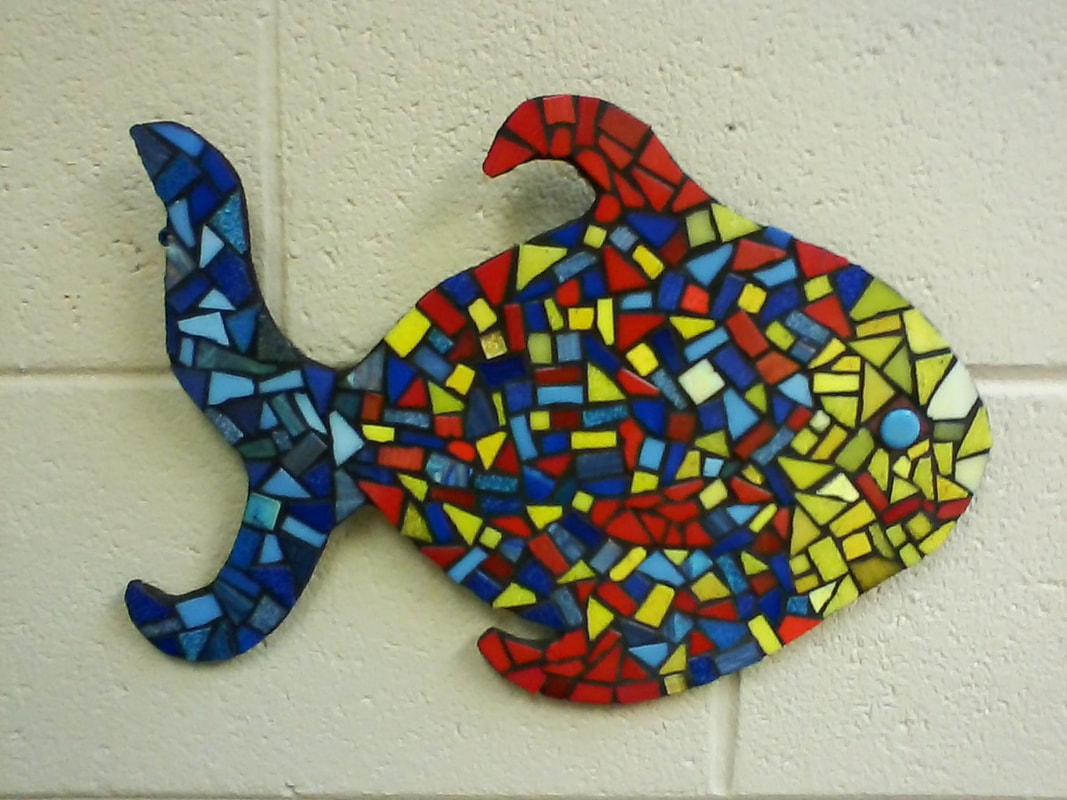

As many of my friends know, I recently made a bunch of mosaic fish, one of which is shown here. I had fun with the project, but found this fish particularly satisfying to make.

Why? Because it’s made of scrap. For most of our projects, Lorraine Meade and I use glass tiles that we purchase online, cutting them into the shapes we want. The scraps from those projects get tossed together in a drawer that gives people learning mosaics something to practice with. This fish used only one round tile from our “good” collection; the rest was from the drawer.

I like making a mosaic when I am restricted by supply, because it challenges my creativity to have those restrictions. This is, I think, a part of my personality. In many ways I prefer working within the finite instead of having infinite possibilities.

Journalism, for example, turned out to be a good “fit” for me because it offered a series of short-term goals: the daily/weekly deadline. Write, publish, move on. I used to look at Tom’s law work, with cases coming back on appeal and the same issues recurring year after year, and think the never-ending process would drive me mad. In fiction writing, I favor the compact short story and the need to hone that prose over the expansive novel. (I also prefer sonnets and haiku over free verse.) I’m okay with island cooking that requires me to alter recipes according to what I can find, rather than dashing over to Provo for ingredients. I’ve never aspired to a large estate or a customized house; like a cat, I enjoy fitting into whatever space is available. And I don’t want to live forever. The thought of a finite life is more comforting than immortality.

Perhaps that’s all just me, but I suspect that there are other “finites” out there, as well as the opposite: people who abhor working and living within set parameters, who long to break out, stretch out, live large and keep on going into the hereafter. And that brings me to a theory about island life.

The theory is that those who either love or don’t mind the finite do better at island living. Islands themselves are finite, ending on all sides at the beach. Somewhat remote ones, like North Caicos, put up all sorts of barriers to the things people want to do, such as find meaningful work, have an active social life, explore the world (both physically and intellectually), raise happy families and be creative in art and the kitchen. Some will thrive within the restrictions, finding happiness despite (or maybe because of) the barriers, while others will long to be set free and won’t find their bliss until they are at sea, abroad or convinced that heaven awaits them.

I’m still thinking about this theory. Some parts of it make sense (and explain things like Clifford Gardiner’s desire to fly), but I could also be all wet, having walked off the edge of the island into the sea.

I welcome comments on my working theory, both those who boost it and those who disagree. Meanwhile, thinking of North Caicos history. I find it cool that John Glenn, one of those infinite types who reached for the stars, splashed down in the Turks and Caicos and first touched land again on an island, Grand Turk. Talk about the best of both worlds!

Why? Because it’s made of scrap. For most of our projects, Lorraine Meade and I use glass tiles that we purchase online, cutting them into the shapes we want. The scraps from those projects get tossed together in a drawer that gives people learning mosaics something to practice with. This fish used only one round tile from our “good” collection; the rest was from the drawer.

I like making a mosaic when I am restricted by supply, because it challenges my creativity to have those restrictions. This is, I think, a part of my personality. In many ways I prefer working within the finite instead of having infinite possibilities.

Journalism, for example, turned out to be a good “fit” for me because it offered a series of short-term goals: the daily/weekly deadline. Write, publish, move on. I used to look at Tom’s law work, with cases coming back on appeal and the same issues recurring year after year, and think the never-ending process would drive me mad. In fiction writing, I favor the compact short story and the need to hone that prose over the expansive novel. (I also prefer sonnets and haiku over free verse.) I’m okay with island cooking that requires me to alter recipes according to what I can find, rather than dashing over to Provo for ingredients. I’ve never aspired to a large estate or a customized house; like a cat, I enjoy fitting into whatever space is available. And I don’t want to live forever. The thought of a finite life is more comforting than immortality.

Perhaps that’s all just me, but I suspect that there are other “finites” out there, as well as the opposite: people who abhor working and living within set parameters, who long to break out, stretch out, live large and keep on going into the hereafter. And that brings me to a theory about island life.

The theory is that those who either love or don’t mind the finite do better at island living. Islands themselves are finite, ending on all sides at the beach. Somewhat remote ones, like North Caicos, put up all sorts of barriers to the things people want to do, such as find meaningful work, have an active social life, explore the world (both physically and intellectually), raise happy families and be creative in art and the kitchen. Some will thrive within the restrictions, finding happiness despite (or maybe because of) the barriers, while others will long to be set free and won’t find their bliss until they are at sea, abroad or convinced that heaven awaits them.

I’m still thinking about this theory. Some parts of it make sense (and explain things like Clifford Gardiner’s desire to fly), but I could also be all wet, having walked off the edge of the island into the sea.

I welcome comments on my working theory, both those who boost it and those who disagree. Meanwhile, thinking of North Caicos history. I find it cool that John Glenn, one of those infinite types who reached for the stars, splashed down in the Turks and Caicos and first touched land again on an island, Grand Turk. Talk about the best of both worlds!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed